Diversity and inclusion in Lived Experience or exclusion and lateral violence against the most vulnerable

Resource competition can encourage denigrating and marginalising other groupings below them, leading to lateral violence. Not being included in any groups makes you even more vulnerable to these attacks.

Lateral violence is a term widely used for peer-on-peer violence within many marginalised groups, and this is where I believe lived experience could be heading.

Introduction

I am Graeme Holdsworth, and I'm a suicide attempt survivor.

I am also a Member of many committees, Lived Experience reference groups, Expert Advisory groups and boards.

I am not here representing any of those today, but I can assure you they are all aware of what I'm about to say.

I did the presentation myself, so it is not a complex PowerPoint presentation, but I have written it out because words are important. Then again, because I'm dyslexic, who knows?

A while ago, I talked at another forum about diversity and inclusion and the diverse nature of lived experience in suicide prevention. However, I doubted that diversity and inclusion were working as they should.

As a suicide attempt survivor, my concerns were about the lack of focus and attention shown to us.

Ironically, I believe that the increased focus on Lived Experience, which is also part of this Conference, and the additional emphasis on suicide prevention is working against suicide attempt survivors.

As in any grouping, power imbalance and the ability to make your voice heard dictates the influence you have.

If this is not equal, there is a real chance that instead of the group being inclusive, it will exclude the most vulnerable.

This sort of exclusion is what I believe is currently happening within lived experience.

As opposed to the bereaved, our grouping is not known to organise. We don't normally advocate for ourselves, partly because withdrawal can be an integral part of the trauma, plus the shame and stigma that flows from the event.

While lived experience includes Suicide Attempt Survivors, Bereaved, and Carers, who from this group speak for lived experience is seldom evident.

I finished the talk with the fact that we have created a hierarchy that isn't helpful.

Now I thought my comments were not all that controversial, but I was sent straight to the Naughty Corner.

Some members of the lived experience sector accused me of insulting and dividing lived experience by raising the topic.

I, therefore, decided to use this session to defend my stance. I will concentrate on data and priority populations where I believe suicide attempt survivors don't get the recognition they deserve and are therefore discriminated against.

And I will expand on why I think there were accusations about insulting lived experience.

DEFINITIONS

A good starting point is definitions; for suicide attempt survivors, two crucial definitions exist. One about lived experience and another concerning data collection

Slide 1 DEFINITIONS

Lived experience of suicide is defined as having experienced suicidal thoughts, survived a suicide attempt, cared for someone through suicidal crisis, or been bereaved by suicide.

Self-harm is defined as "an act in which a person harms themselves with a motive that may or may not involve the intention of ending their life, and survives."

The definition of self-harm includes but is broader than suicide attempts. The distinction relates to intent.

It acknowledges that some people may self-harm with suicidal intent, whereas others may self-harm for emotional relief, or as a means of coping with distressing thoughts or feelings, or for other reasons.

The problem with this definition is that intent of self-harm is essential to collect data on suicide attempt survivors.

So, rather than just acknowledging the uncertainty around determining intent, we should, through better research, statistics and data, identify suicide attempts contained in the self-harm data.

With the self-harm definition, we will never get suicide attempt data.

Slide 2 AIHW

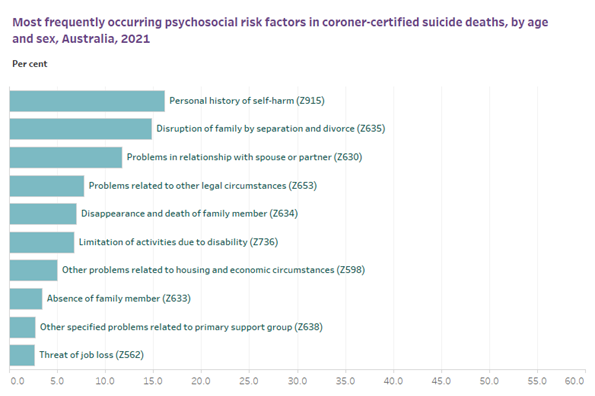

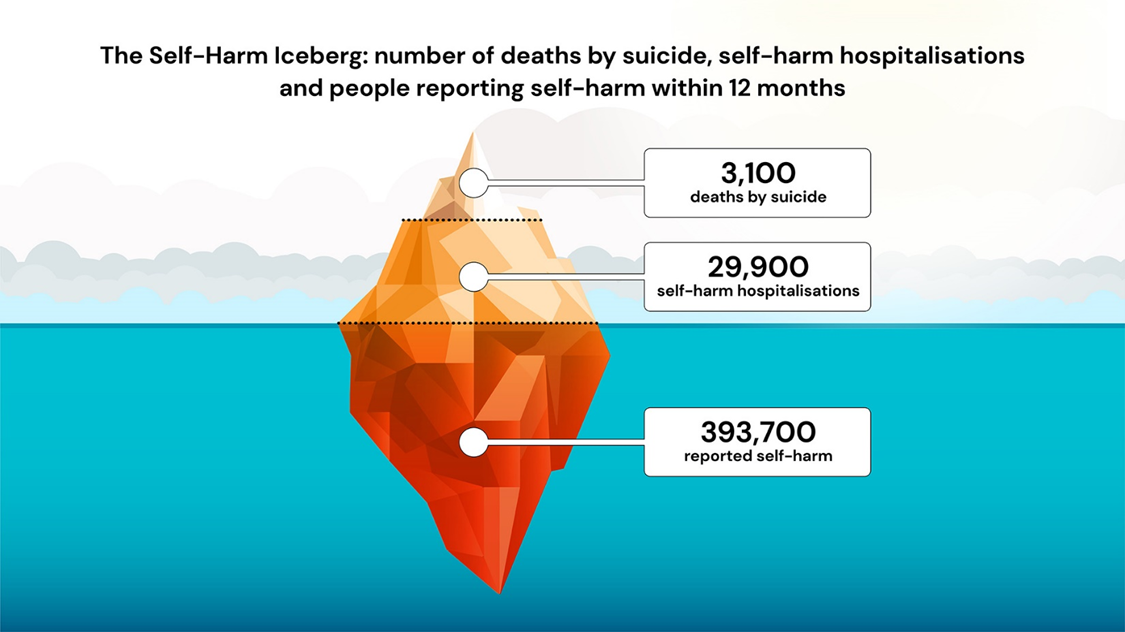

Figures for males

Figures for females

These are from the National Suicide and Self-harm Monitoring System

They represent the most frequently occurring psychosocial risk factor in coroner-certified deaths, by age and sex, Australia, 2020, for males and females.

At the top of that list, which is the highest risk factor, in both cases, is a personal history of self-harm.

This should be low-hanging fruit and an excellent place to reduce suicides, but again we must first identify the intent of the self-harm.

We all know that suicide attempters can have a history of several attempts. I subscribe to the Thomas Joiner's theory on Why People Die by Suicide. That is, a person works up to suicide through suicide attempts to overcome the fear of death and the instinct for self-preservation.

How much do we know about these suicide attempts that lead to the most significant psychosocial risk factor of suicidal deaths? The answer is very little.

We used to know that over 65,000 people in Australia attempt to take their lives every year, but this figure is now many years old and outdated.

The most recent ABS data showed 53,000 Australians had attempted to take their own life over the past 12 months. This sounds like a reduction, but the range was from 15,000 to 92,000 attempts.

These numbers were not widely published because the error rate of 15,000 to 92,000, that is, 25% to 50%, was too high. The ABS is going to try again next year.

But for the first time, the same ABS data estimated the prevalence of self-harm.

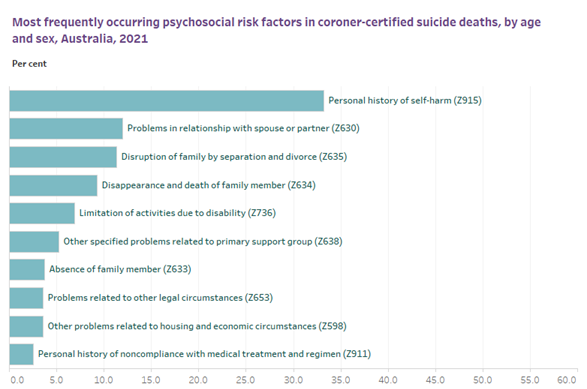

Slide 3 BLACK DOG

This comes from a Black Dog Institute document called

"The Self-harm Iceberg Reveals Hidden Depth"

Authored by Helen Chistersen and others

As you can see, this shows that just on 400,000 self-harms occur each year that didn't report to a hospital.

As mentioned, suicide attempts are part of and included in those figures.

Also, as you can also see that under 10% of self-harms were hospitalised. This is important as it indicates a significant shortfall when relying on ambulance data to try and estimate suicide attempts and the hospital-based model of the aftercare system.

So, we now know that suicide attempts are somewhere between 15,000 and 400,000, but we have no idea what the figure is because we do not measure the suicidal intent of self-harm.

This is not good enough, as there are a lot of consequences that flow from the lack of suicide attempt data.

Data

In suicide prevention, data and statistics are important. They are essential to the evidence-based nature of our services.

Evidence base systems are derived from combining data and research, which then informs and initiates funding and services. The continued cycling of data, research and funding is how services develop and grow.

Not only don't we know how many suicide attempts there are, but we also don't know where they occur, who the attempters are, or what contact they have had with the Government and other services before or since their attempt. So we know very little about them, and to a large extent, the lack of data is intentional because we only collect data from limited sources.

We need to fill these data gaps by including suicide attempt data held by police and other emergency services, general practitioners, and community services, not just ambulances.

We need to improve the collection of attempts data from Emergency Departments by developing protocols for intent. There is also current data available from the existing Aftercare sector. Other countries do this, including New Zealand.

It would be nice if the National Suicide and Self-harm Monitoring System became the National Suicide, Suicide Attempt and Self-harm Monitoring System. That would definitely be an improvement.

It has always amazed me that after my attempt, I was in contact with the police; in fact, I spent my first night after my attempt in a police station. After that, on numerous occasions, the local and state mental health authorities, my GP and psychiatrist, and I ended up in a private psychiatric institution. Still, my name would not appear in any data system as a suicide attempt.

Aftercare, as limited as it is, is a critical service for suicide attempt survivors. It keeps us alive.

Evidence from existing aftercare models shows that suicide attempts are problematic for referrals, with ongoing data gaps around self-harm and suicidal behaviour crucial and the key to aftercare problems.

All referral processes for aftercare require hospitals and health professionals to refer suicide attempt survivors.

So it is no wonder that aftercare services have issues with their eligibility and referral process because it needs someone at a hospital to decide that the intent of the self-harm was a suicide attempt.

Priority Population.

Apart from data, the Suicide Prevention Sector also uses priority groups to designate significant grouping or those who need special attention.

Your standing in these groupings can be critical to the level of funding and research and the group's influence in the sector.

Government and other organisations develop numerous priority groups and at-risk groups lists. The bereaved and carers are included in these groups and lists, but suicide attempt survivors don't make it.

All priority populations, like First Nation or LGBTQI+, have suicide attemper survivors within their groups, but they are not established to represent them.

While we don't know the exact number of suicide attempts, we know the scale and that many of those will make another attempt. So, therefore, that should put suicide attempt survivors at the top of the lived experience at-risk priority population list, yet they don't make it onto any at-risk group lists that I have found.

These priority lists create a hierarchy, and this can create competition between groups, especially against the groups below you on the totem pole.

Resource competition can encourage denigrating and marginalising other groupings below them, leading to lateral violence. Not being included in any groups makes you even more vulnerable to these attacks.

Lateral violence is a term widely used for peer-on-peer violence within many marginalised groups, and this is where I believe lived experience could be heading.

Contempt

Humans have a vast reservoir of what are sometimes called reactive moral emotions: anger, resentment, shame and, of course, contempt.

Contempt is essential to this conversation, probably more critical than stigma when it comes to how we treat each other.

Arrogance and entitlement are the fathers of contempt, and it is judgemental.

Comments like "we are trying to stop people being like you" or "you are the problem, not the solution" categorise groups rather than a particular person's actions or character traits.

Contempt deems its objects morally inferior, thereby confirming the standing of the one showing contempt.

It encourages us to act in specific ways towards its object, which may include ridicule, humiliation, disgust or ostracism.

It reflects a hierarchical order. It does not require those held in contempt to do anything in particular. On the contrary, it requires them merely to hold a position, irrespective of how they got there.

Because suicide attempt survivors are sometimes held in contempt, they are marginalised and discriminated against and are at risk of lateral violence.

Understanding lateral violence helps us identify stigma, contempt and other harmful narratives and allow us to improve the role of lived experience from a place of empathy and compassion.

Stigma against and contempt of any part of our community impacts all of us.

Conclusion

This is probably one of the last of these sorts of talks I will be giving. The last couple of months haven't been easy.

However, I hope I have inspired other members of our suicide attempters tribe to come out of the shadows, be prepared to fill this uncomfortable space and start their talks with, "I am a suicide Attempt Survivor,"

Thanks